Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie: Women’s Health, Truth-Telling, and the African Diasporic Voice in Dream Count

By Sarah Laaru and Khaya Ronkainen on behalf of the Finnish-African Society

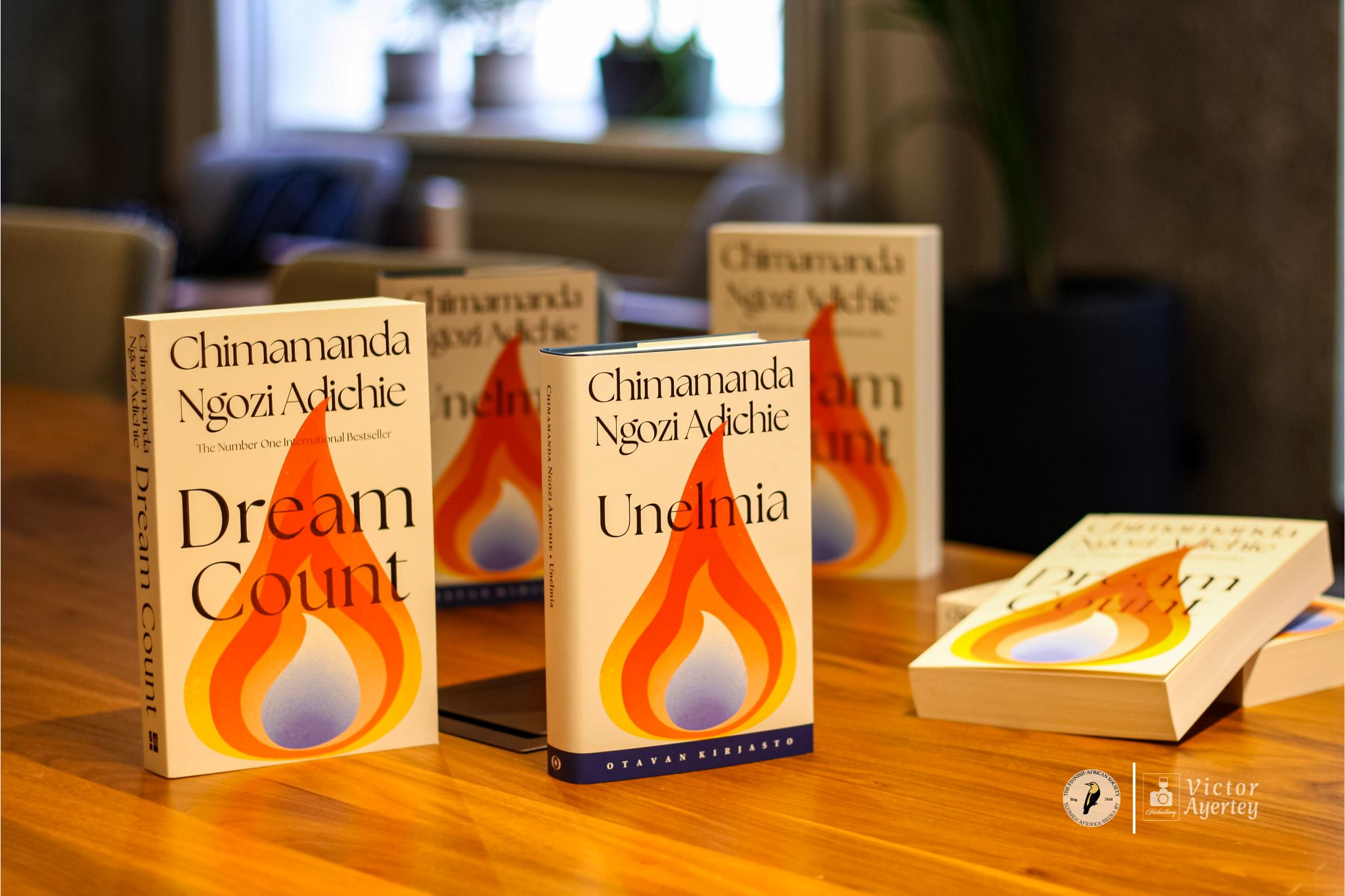

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie needs no introduction; her accomplished body of work speaks for itself. The significant buzz surrounding her latest novel, Dream Count, made her visit to Helsinki an eagerly anticipated event among her devoted readers. Though recovering from near-total vocal strain, Adichie graciously made time for an interview.

The atmosphere is warm and welcoming from the start. Greeting Adichie in Igbo, her native language, offers more than linguistic familiarity; it makes our conversation feel intimately familiar, like a warm homecoming. The circumstances of our meeting — a voice temporarily subdued yet resolved to be heard — embody the recurring themes found throughout Adichie’s work.

Much like her other works, Dream Count unearths the ways broader cultural discourse often flattens, silences, or distorts women’s voices and immigrant experiences. On this Helsinki spring afternoon, Adichie shares insights on how storytelling can transform silence into revelation, absence into presence, fragmentation into wholeness, fostering healing and shared understanding.

Set against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, Dream Count intricately weaves the stories of four distinct women: Chiamaka, Omelogor, Zikora, and Kadiatou. The novel uses multiple voices, time-frames, and locations as it explores a range of themes central to women’s lives, including health, memory, generational ties, maternal love, immigrant experiences and the multifaceted nature of their experiences. It’s a poignant exploration of interconnected journeys that evokes a range of emotions, from sympathy to rage, but ultimately delivers a sense of healing and peace. This novel is a gift of reflection.

Reclaiming Women’s Health Narratives

The literary landscape often pushes the themes surrounding women’s health to the margins. But Dream Count openly addresses these issues; it refuses to look away. In the novel, Adichie honours the truths about women’s bodies. Menopause, fibroids, hysterectomy, and menstruation are not side notes, but central to the characters’ realities and emotional truths.

Women’s health is also an under-represented topic and often taboo in the African context. We ask the author what compelled her to address these issues and what she hopes her female readers take away from this depiction of bodily realities.

Adichie responds, “Why did I? Because I think it’s important. And you’re right, it’s under-represented. I think there’s so much silence. It’s a silence that is loaded with shame. In some ways, it’s as if women are held responsible for things that are beyond their control.” The author highlights the unfair burden placed on women, and thus confronting these issues in Dream Count is a way of uncovering the truth and refusing shame. She stresses, there’s nothing to be ashamed of.

Studies show that almost 80% of African women develop fibroids by the age of 50. Dream Count confronts the cultural shame surrounding menstruation, fibroids, and hysterectomies. The novel, in many respects, is a literary act of resistance. It offers solidarity and a space for women to rethink how to advocate for their health needs.

Fiction as Empathy and Truth-telling: The Immigrant Story Retold

Known for her belief in fiction’s capacity to cultivate empathy, Adichie once said, “Journalism tells us what happened. Fiction tells us how it felt, and there’s power in knowing how something feels often.”

In Dream Count, the immigrant stories are not flattened. We see characters like Omelogor and Kadiatou grapple with complex issues: invincibility, uncertainty, and the negative connotations of being labelled an “immigrant”. By focusing on Kadiatou’s humanity, Adichie pushes back against the media’s reductive headlines and their shortened version of her story.

The immigrant experience in journalism is frequently portrayed as a single story, lacking nuance and with little compassion, often omitting crucial details and distorting the truth. Dream Count beautifully reveals the emotional and psychological effects of what these headlines can hold.

“When I’m writing fiction, I do not think I shall now re-educate people. But I feel strongly when it comes to immigration, especially African people, and how they’re portrayed in the Western discourse. It’s not just about feeling hurt. It’s also about telling the truth.”

Responding to our curiosity about whether this was a message she wanted to convey, Adichie explains she doesn’t write intending to educate readers. However, her motivation to write about Kadiatou, a character partly based on Nafisatu Diallo (a central figure in a high-profile case), stemmed from feeling hurt by the media’s coverage. It made her think of many women who had faced a similar ordeal.

“It’s enraging and annoying, but also, it always felt wrong. Sometimes people are no longer people. They’re just very flat things,” Adichie remarks, reflecting on how African immigrants are often portrayed in Western media. “It’s forgotten that you’re a person who laughs, cries, dreams and thinks.”

This statement functions as both a critique and a creative mission. Through our conversation about her latest novel, it becomes clear that Adichie’s storytelling is focused on restoring this missing dimensionality by adding depth and authenticity to women’s experiences in a way journalism and public dialogue rarely do. By so doing, she creates a truthful world through fiction where nuanced lived experiences can flourish, unburdened by reductive stereotypes and oversimplified narratives.

The Power of Language: Mother Tongue in Diaspora Literature

The characters in Dream Count showcase the author’s mother tongue in a beautiful and integral way. For Adichie, language is more than dialogue; it’s identity. Regarding the significance of mother tongues in African literature for the African diaspora, Adichie notes that while it’s important, its importance is ultimately personal.

“I think it’s important, but it has to be important to you. In other words, I don’t think every writer must use it.”

She shares that her breakthrough novel, Purple Hibiscus, was born from homesickness and creative honesty. Set in a small Nigerian town with a strong Igbo presence, the novel was unlike anything else on the American literary market at the time. The author states, “I wanted to create a home. I was trying to capture that idea of constantly negotiating two languages.”

Adichie’s international readers recognise a duality in her world, reflected in her storytelling by characters who often speak two languages. She suggests that using the mother tongue must be genuine, accurately represent the characters’ lives, and avoid confusing readers unfamiliar with the dialect. In her words, the story has to be truthful.

Don’t Apologise for Your Story: A Message to Emerging Writers

As part of our work at the Finnish-African Society, we promote and offer our African diaspora writers an opportunity to establish themselves in the Nordic literary scene. A common struggle for emerging writers is overcoming self-doubt, the weight of cultural expectations, suppressed ambition, and fears about audience reception of their stories.

When asked for a message to encourage emerging writers, Adichie acknowledges the internal conflicts many face before finding their authentic voice. She understands the fear and concern that comes with this creative journey, candidly sharing that her first attempt at writing after moving to the United States was what she calls ‘a terrible book’. Notably, it wasn’t Purple Hibiscus, the acclaimed novel that would eventually launch her literary career.

The anxieties and worries of emerging writers facing these challenges are quite understandable and common, and her message is clear.

“Don’t apologise, don’t water it down. Don’t think, if I write about this, the Western audience will not understand. Let’s tell the truth of our experience. Let’s not worry about writing what we think they want to read.”

Adichie further explains that sometimes gatekeepers don’t understand how open-minded readers can be. Eventually, Purple Hibiscus was published by a small press and weeks later became an independent bestseller.

In Dream Count, memory isn’t merely a storytelling device or a series of flashbacks; it fundamentally shapes the characters’ realities, emotional truths, and imagined futures. It presents readers with a nuanced path towards healing, prompting reflection on potential “what if?” — a question that torments and heals in equal measure. As the characters do in their inner worlds, they ask hard questions and face their pains with unflinching truths.

Adichie offers a narrative that demands to be read, shared, and spoken aloud. It’s a novel that invites dialogue around memory, migration, womanhood, and the quiet revolutions of everyday life. This is a remarkable achievement, especially for those who have long admired her work. For new readers, it serves as a compelling introduction to a literary icon, whose work continues to challenge and transform the literary landscape.

At the heart of her work is the commitment to truth, not just to what happened but to how it felt. As the author once stated, “We can’t lose hope and give in to despair. One way to cope is to open a book.” Let this book find its way into your hands, communities, and libraries. Let it ignite those long-overdue conversations. Above all, may it remind us of fiction’s enduring power to heal, bear witness, and envision new futures.